Andrew King, The University of Melbourne

The Bureau of Meteorology recently announced a negative Indian Ocean Dipole event is underway.

But what does that mean and how does it affect Australia’s weather? Will we get a reprieve from the flooding rains of recent months?

For many places across the east coast, the answer is no. Spring won’t bring a clean break from this year’s very wet winter.

Warmer waters around Australia equals more rain

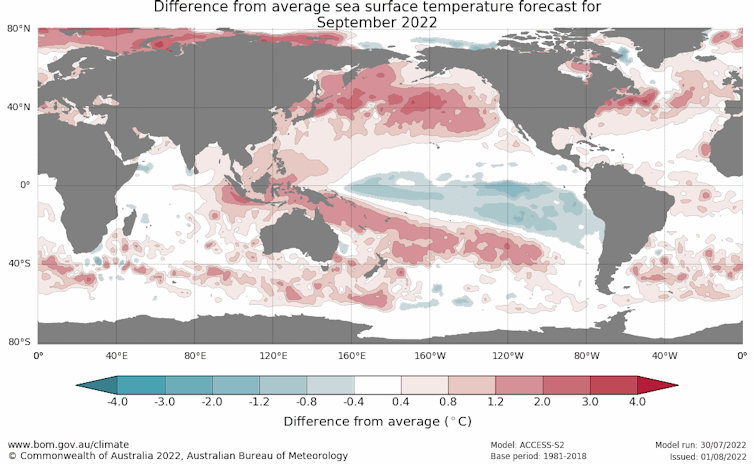

The negative Indian Ocean Dipole, or IOD, has been declared because ocean temperatures are warmer in the tropical east Indian Ocean than in the west Indian Ocean.

The Indian Ocean Dipole is a type of year-to-year climate variability, a bit like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, but in the Indian Ocean rather than the Pacific.

Once it goes into a particular phase, it usually remains in that phase for a few months. This persistence in sea surface temperature patterns results in predictability in Australian climate conditions.

When we have negative Indian Ocean Dipole conditions we tend to see more rain over southern and eastern Australia.

The Indian Ocean Dipole relationship with Australian rainfall is strongest in September and October, so we’re likely to see wet conditions over the next few months at least.

Warm waters in the east Indian Ocean, like we’re seeing at the moment, increase the occurrence of low pressure systems over the southeast of Australia as well as the amount of moisture in the air.

This means there’s a higher likelihood of rain generally and an increased chance of extreme rain events too.

When will the rain stop?

Another wet outlook is alarming for many people in eastern Australia who have suffered through wetter than normal conditions since 2020.

We’ve seen back-to-back La Niña events and a negative Indian Ocean Dipole in 2021’s winter.

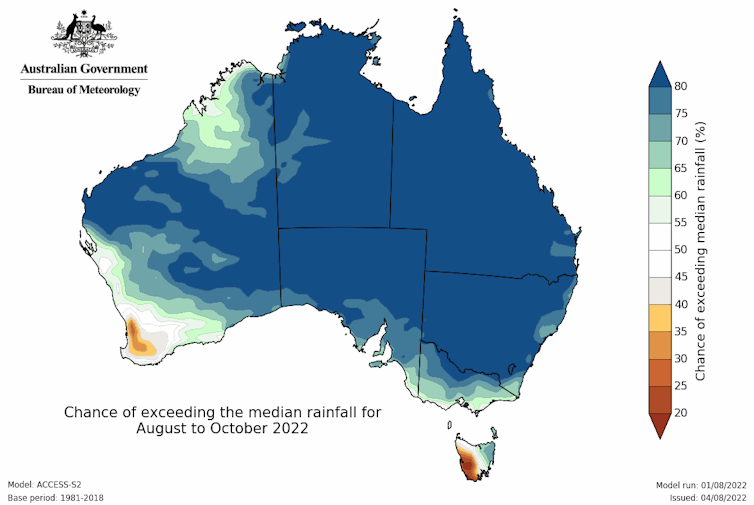

The negative Indian Ocean Dipole is showing its influence in the Bureau of Meteorology’s seasonal predictions. Wetter than normal conditions are forecast for the coming months throughout the east of the continent.

This also happens to be the time of year when seasonal outlooks tend to be most skilful. In the summer, more rain falls in storms and small-scale systems that are harder to forecast well in advance. In winter and spring the outlooks tend to be a bit more accurate but are not always perfect.

Unfortunately, after two consecutive La Niña summers it is also looking increasingly likely we’ll see another La Niña form later this year.

Three La Niña events in a row is not unprecedented but it is unusual. The increased chance of another La Niña raises the odds of wetter conditions persisting for a few more months at least.

Have we seen the end of the cold weather?

We saw a cold start to winter in the southeast of Australia. Since then temperatures have been below normal across much of northern Australia.

Nationally, we had the coldest July for a decade, but in the past this would have been an unremarkable event as it was only slightly cooler than historical averages.

As we leave the coldest part of winter behind the temperatures will inevitably rise, although we could still have another cold spell.

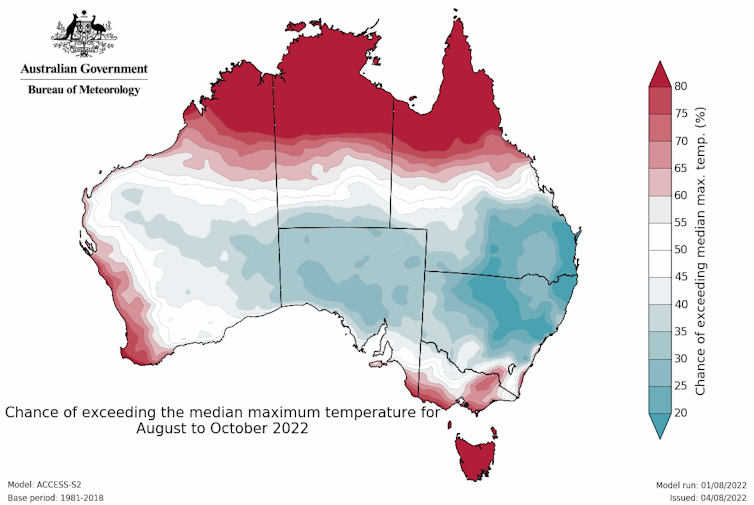

The Bureau’s seasonal outlook suggests warmer than average daytime temperatures are likely for the north and southern coastal areas. Other areas may be cooler than normal as increased cloud cover and rain are likely to suppress temperatures.

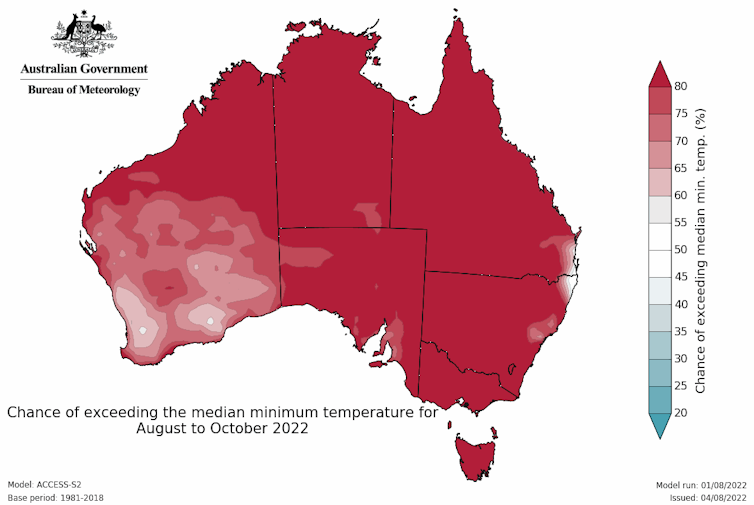

On the other hand, minimum temperatures are likely to be above normal across the country. Increased cloud cover and rain tends to be associated with warmer nights as the cloud prevents the ground from cooling rapidly overnight. This reduces the chance of frost.

Is the constant rain a result of climate change?

For parts of New South Wales, the news of wet conditions being on the cards could not come at a worse time. Sydney and other areas of the eastern seaboard have already received record-breaking rain totals so far this year, including in July. Catchments remain saturated so further rainfall may well lead to more flooding.

Australia has highly variable rainfall and we have seen multi-year spells of persistent wet conditions before – notably in the mid-1970s and 2010-2012.

There isn’t a strong trend in rainfall in the areas that have been devastated by floods and it’s only three years since we saw the driest year on record in New South Wales.

The jury is still out on how climate change affects rainfall over most of Australia.

It is vital we build a better understanding of rainfall changes under global warming so we can plan better for our future climate.![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.