Andrew King, The University of Melbourne; Celia McMichael, The University of Melbourne; Harry McClelland, The University of Melbourne; Jacqueline Peel, The University of Melbourne; Kale Sniderman, The University of Melbourne; Kathryn Bowen, The University of Melbourne; Tilo Ziehn, CSIRO, and Zebedee Nicholls, The University of Melbourne

The world’s focus is sharply fixed on achieving net-zero emissions, yet surprisingly little thought has been given to what comes afterwards. In our new paper, published today in Nature Climate Change, we discuss the big unknowns in a post net-zero world.

It’s vital that we understand the consequences of our choices when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions and what comes next. The pathways we choose before and after reaching global net-zero emissions might mean the difference between a planet that remains habitable and one where many parts become inhospitable.

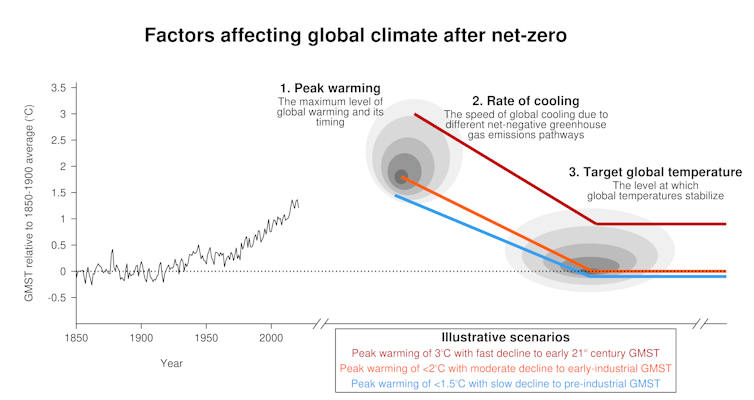

At the moment, human activities have a warming effect on the planet. But achieving our climate policy goals would take humanity into the uncharted territory of being able to cool the planet.

Being able to cool the planet raises a number of questions. Principally, how fast would we want the planet to cool, and what global average temperature should we aim for?

How are our emissions changing?

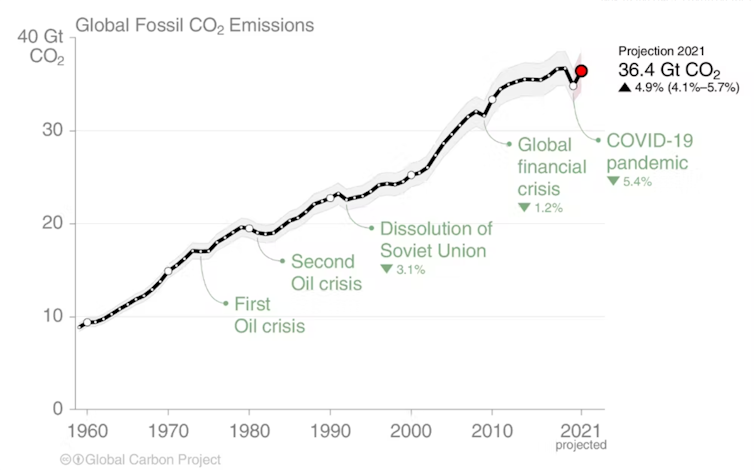

Our collective greenhouse gas emissions have warmed the planet about 1.2℃, relative to pre-industrial temperatures. In fact, despite all the talk about reducing emissions, global carbon dioxide emissions are at near-record levels.

Some countries have successfully reduced their greenhouse gas emissions in recent years, such as the United Kingdom which has halved greenhouse gas emissions relative to 1990.

There is also greater push from major emitters such as the United States and the European Union – as well as countries that emit less but already experience climate change impacts – to take stronger steps to limit the damage we are doing to the climate.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and reaching net-zero are humanity’s greatest challenges. As long as greenhouse gas emissions remain substantially above net-zero we will continue to warm the planet.

To be in line with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to well below 2℃ above pre-industrial levels this century, we need to drastically reduce our emissions.

We also need to increase our uptake of carbon from the atmosphere through developing and implementing drawdown technology.

What will come after net-zero?

Net-zero emissions will be reached when humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere are balanced by their removal from the atmosphere. We would likely need to reach global net-zero well within the next 50 years to keep global warming well below 2℃.

If we achieve this, we could continue the process of decarbonisation to reach net-negative greenhouse gas emissions – where more of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions are removed from the atmosphere than released into it.

This would need to be achieved through a combination of “negative emissions” technologies, likely including some not invented yet, and land use changes such as reforestation.

Continued net-negative emissions will cause the planet to cool as greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere fall. This is because the greenhouse effect, where gases such as carbon dioxide absorb radiation from Earth and warm the atmosphere, would weaken.

Currently, there’s almost no focus from governments, or indeed scientists, on the consequences of meeting our policy goals and going beyond net-zero. But this would be a turning point as the world would begin to cool.

Land would cool faster than the ocean. Indeed, some people may experience substantial cooling over their lifetimes – an unfamiliar concept to grasp in our warming climate.

These changes would be accompanied by effects on weather extremes and impacts to weather and climate-sensitive industries. While there’s not much research on this yet, we could, for example, see shipping routes close up as ice regrows in polar regions.

In the long-term, the best target global temperature for the planet might be something akin to a pre-industrial climate, with the human effect on Earth’s climate receding.

In our paper we call for a new set of climate model experiments that allow us to understand the range of possible future climates after net-zero.

Any decisions must be informed by an understanding of the consequences of different choices for a post net-zero climate. For example, competing interests between countries and industries may make global agreements more challenging in a post net-zero world.

Why does this matter now?

Reading this article, you may feel we’re getting ahead of ourselves. After all, as highlighted, global greenhouse gas emissions remain at near-record highs.

A key factor that will affect the behaviour of the climate system after net-zero emissions would be the maximum level of global warming that we peak at. This is dictated by our current and near-future emissions.

If we fail to meet the Paris Agreement and peak global warming reaches 2℃ or more, then future generations will endure the effects of higher sea levels and other possible disastrous climate changes for many centuries to come.

Our understanding of post net-zero impacts of different peak levels of global warming is extremely limited.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions through decarbonisation remains our key priority. The more we can suppress global warming by reaching net-zero emissions as early as possible, the more we limit potential disastrous effects and the need to cool the planet in a post net-zero world. ![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne; Celia McMichael, Senior Lecturer in Geography, The University of Melbourne; Harry McClelland, Lecturer in Geomicrobiology, The University of Melbourne; Jacqueline Peel, Director, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne; Kale Sniderman, Senior Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne; Kathryn Bowen, Professor – Environment, Climate and Global Health at Melbourne Climate Futures and Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, The University of Melbourne; Tilo Ziehn, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO, and Zebedee Nicholls, Research Fellow at The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.