The Australian Bureau of Meteorology has announced a high likelihood of a La Niña developing in Spring 2022, which would mark a rare triple dip La Niña.

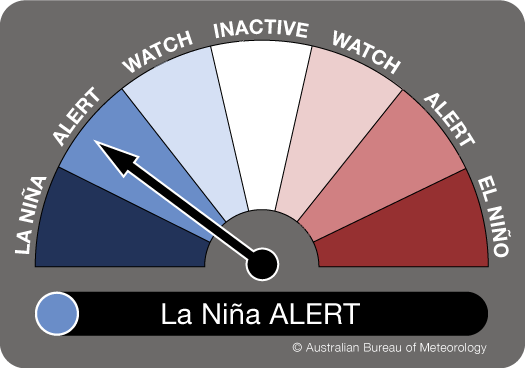

The Bureau of Meteorology (‘the Bureau’) has moved from ‘La Niña WATCH’ to ‘La Niña ALERT’ with the likelihood of La Niña returning this spring increasing to around 3 times the normal risk.

Climate models and indicators have shifted towards meeting La Niña ALERT criteria. A La Niña ALERT means the chance of a La Niña developing in the coming season has increased.

When La Niña criteria have been met in the past, a La Niña event has developed around 70% of the time.

Climate Driver Update – Wet outlook continues with an increased chance of La Nina developing this spring

In an article and briefing note for decision makers earlier this year, Dr Zoe Gillett explained what a La Niña is.

“La Niña is an ocean temperature and wind pattern across the Pacific Ocean. It has global impacts and promotes increased rainfall over much of Australia. Eastern Australia has experienced extreme rainfall and flooding associated with La Niña for two consecutive summers. These events have affected entire communities across large parts of the country and impacted our agriculture and supply chains. La Niña in two consecutive summers – what we call a double-dip La Niña – is not uncommon and happens in about 50% of events. This persistence can increase climate risks due to increased rain falling on already saturated catchments” says Dr Gillett.

A range of experts at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes have responded to the Bureau’s announcement of a La Niña alert.

Dr Agus Santoso explained to ABC’s PM program how often these triple dip events occur:

“A triple La Niña is actually quite rare. It has happened two times since 1950”

Dr Agus Santoso

While Dr Linden Ashcroft spoke to ABC News Breakfast about the the factors that come to play in the formation of a La Niña.

“La Niña kind of primes the atmosphere for rainfall to occur. It means we’ve got warmer than normal ocean temperatures off the north east coast of Australia and actually we’ve got them off the north west coast as well…the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean are in step which means even wetter conditions”

Dr Linden Ashcroft

Professor Matthew England told The New Daily that large parts of the country are “primed for flooding”.

‘‘The soil over some of these areas is not even dried up from the rains of the last couple of years. So, it is really primed for more flooding and that is a concern,’’ he said.

‘‘These triple events can be very impactful because you are not seeing the drying out of the soil and then more rain.’’

Is it climate change?

Dr Andrew King told the Sydney Morning Herald that it’s harder for scientists to unpick the role of climate change right now in relation to La Niñas.

“Climate change is having big effects in terms of heatwaves and things like that, but in terms of rainfall variability and La Nina and El Nino, it is harder to see the climate change element at the moment,” he said.

“We need to see these things that occur every few years and we need to have long-term record observations to build a pattern and we don’t have that yet.”

Dr Zoe Gillett says it’s more likely we’ll swing between extremes in future.

“Multi-year La Niña events might be predictable more than a year in advance based on the strength of the preceding El Niño event. El Niño is the opposite to La Niña and usually leads to reduced rainfall over eastern Australia. However, the current La Niña event is puzzling because it developed without a previous strong El Niño. Scientists will be working to understand its causes over the coming years” says Dr Gillett.

“Most climate models show that in an increased greenhouse warming world we should expect almost double the number of extreme La Niña events compared to last century. We’re likely to swing more often from the extremes of El Niño to the extremes of La Niña. This means swapping from droughts to flooding rains more often, but we do have to interpret these climate models with care. The models are getting better, but to help governments, industries and communities prepare for a future with more extremes, we need to keep developing the modelling and the science.”