Originally published by Washington University in St. Louis

The Pacific Ocean covers 32% of Earth’s surface area, more than all the land combined. Unsurprisingly, its activity affects conditions around the globe.

Periodic variations in the ocean’s water temperature and winds, called the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, are a major meteorologic force. Scientists know that human activity is affecting this system, but are still determining the extent. A new study in Nature has revealed that the atmospheric component of this system — called the Pacific Walker Circulation — has changed its behavior over the industrial era in ways that weren’t expected.

An international team of scientists — led by two who worked together at Washington University in St. Louis — also found that volcanic eruptions can cause the Pacific Walker Circulation to temporarily weaken, inducing El Niño-like conditions. The results provide important insights into how El Niño and La Niña events may change in the future.

“What happens in the tropical Pacific doesn’t stay in the tropical Pacific,” said Bronwen Konecky, an assistant professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences at Washington University. “It impacts vast stretches of the world. The Pacific Walker Circulation is a major driver of variability in global precipitation.”

Earth’s rotation causes warm surface water to pool on the western side of ocean basins. In the Pacific, this induces more humid conditions in Asia, with low-altitude trade winds blowing west across the sea. The high-altitude easterlies create an atmospheric circulation — the Pacific Walker Circulation — that drives weather patterns in the tropical Pacific, and far beyond.

Konecky said that when one looks at projections for future climate states for the world, “there’s an incredibly high model agreement, when it comes to future changes in temperature. There is a whole lot less agreement when it comes to future changes in rainfall.”

Climate models generally predict the Pacific Walker Circulation will weaken in response to global warming; however, its recent strengthening suggests that aerosols — the suspension of fine, solid particles or liquid droplets in air — introduced by human activity might have the opposite effect.

“We set out to [determine] whether greenhouse gases had affected the Pacific Walker Circulation,” said lead author Georgy Falster, a research fellow at the Australian National University and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes. “We found that the overall strength hasn’t changed yet, but instead, the year-to-year behavior is different.”

Falster worked with Konecky as a postdoctoral fellow at Washington University. Sloan Coats, at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and Samantha Stevenson, at the University of California, Santa Barbara, are the other authors.

The scientists observed that the length of time for the Pacific Walker Circulation to switch between El Niño-like and La Niña-like phases has slowed slightly over the industrial era. That could exacerbate the associated risks of drought, fire, rains and floods, Falster said.

That said, the authors didn’t notice any significant change in the circulation’s strength — yet. “That was one surprising result,” Stevenson said. “Because by the end of the 21st century, most climate models suggest that the Pacific Walker Circulation will weaken.”

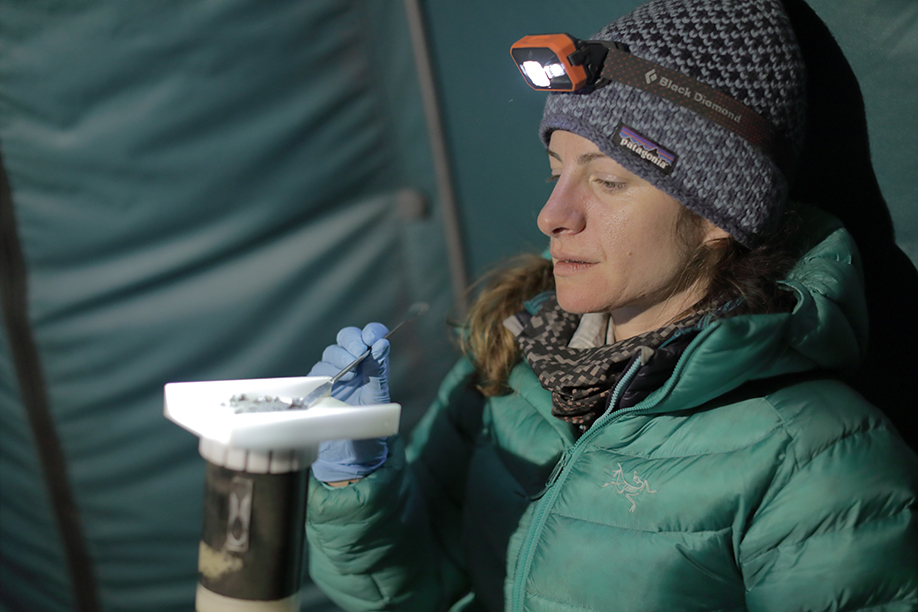

The team used data from ice cores, trees, lakes, corals and caves to investigate the long-term weather patterns of the Pacific over the past 800 years. The scientists combined these datasets with newer observational data, then used statistical methods to build out annually resolved reconstructions of the Pacific Walker Circulation.

“Our study provides long-term context for a fundamental component of the atmosphere-ocean system in the tropics,” Coats said. “Understanding how the Pacific Walker Circulation is affected by climate change will enable communities across the Pacific and beyond to better prepare for the challenges they may face in the coming decades.”

Volcanoes play a clear role

Among climate scientists, there has been a hot debate over the last few years about what the El Niño system does after a volcanic eruption, Konecky said. The Pacific Walker Circulation is the atmospheric component of that system.

“We have long known that large volcanic eruptions, especially from the tropics, tend to cool the planet off for a few years,” Konecky said. “But when it comes to hydroclimate, the impacts are harder to figure out, because rainfall and other hydroclimate variables are so much noisier than temperature. So, it’s just hard to tell: was it a little bit wetter this year because a volcano erupted near Fiji, or for some other reason?”

Volcanic eruptions have the power to impact climate on a global scale, but not every volcano has such impact. Previous research has shown that when there is a strong tropical volcano, the world tends to get a bit cooler.

In terms of potential impact on hydroclimate or rainfall, other scientists have been looking at whether volcanic eruptions change ocean temperatures, because the gradient of ocean temperatures across the tropical Pacific can set the stage for El Niño events. This new study tackles the impact of eruptions head-on by focusing on the behavior of the atmosphere, rather than ocean temperatures. The results were striking:

“Following a volcanic eruption, we see a very consistent weakening of the Pacific Walker Circulation,” Konecky said.

“This is not happening by chance. It’s something that is quite robust,” she said. “We see a consistent response in the atmosphere, whereas others have not seen the same response in ocean temperatures. And that’s either because the atmospheric response is stronger or it’s easier to detect.”

The study was funded in part by the National Science Foundation, under grants AGS-1805141, AGS-1805143, AGS-2041281 and OCE-2202794; and in part by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Portions of this content are courtesy of ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes.